Have you ever searched for the hashtags #bookstagram, #booklover, or #bookworm? If you have, then you know that Instagram is absolutely brimming with Instagram users who not only LOVE books, but love to take gorgeous photos of their books. We wanted to share a few of our favorites (and we really mean just "a few"... there are SO MANY awesome accounts!) with some of our fellow Dear English Major book nerds! Here are 40 of our favorite book Instagram accounts. Enjoy!

How M.A. Classes Differ From B.A. Classes

Towards the end of their undergraduate career, many people turn their sights towards higher education and consider getting an M.A. – I know, I was one of those people!

While getting a master’s degree seems like a logical step to take after graduating with a B.A., there are some major differences between graduate and undergraduate classes that all students should reflect on before making any commitments. I hadn’t really considered these differences until after I joined an M.A. English program, and was in for a big shock when I realized how different M.A. classes can be!

While each program will vary between schools, here are a few general things you can keep in mind when considering another degree:

English Majors: Avoid Making These 3 Common Mistakes on Your Resume

For most people I know, there is a great deal of dread and anxiety around creating or updating a resume. What should I include? How long should it be? What should it look like? And really, it’s not an easy answer—there is no clear-cut way to create a resume. In my experience, they’re all a little different.

But in going over hundreds of English majors’ resumes —whether it’s for Dear English Major or my writing business—I’ve noticed a few mistakes that are made over and over again.

Here are the 3 most common mistakes English majors make on resumes:

Is Your Resume Being Ignored? Here's One Potential Reason Why

Applying for a job is a long and time-consuming process, especially if you’ve tailored your resume and crafted an original, beautiful cover letter (both of which you should be doing!).

Wouldn’t it be a shame if all that hard work went to waste?

Few applicants realize this, but if you're submitting your resume via email, your resume isn’t what gives potential employers their first impression of you. Your email will provide a first impression, and when written poorly, it could cost you a well-deserved career opportunity.

Interested in a Career as a Copyeditor? Read REAL Advice From Copyeditors

While obtaining an English degree can certainly set you on the right path to becoming a copyeditor, it doesn't necessarily mean you're ready to jump in head first to a full-time copyediting job! So what can you do to prepare?

Below, copyeditors with years of hard-earned experience share their advice for how to begin your career in copyediting, where to turn for information, important books to read, and more!

A Veteran’s Perspective on Literature & the English Major

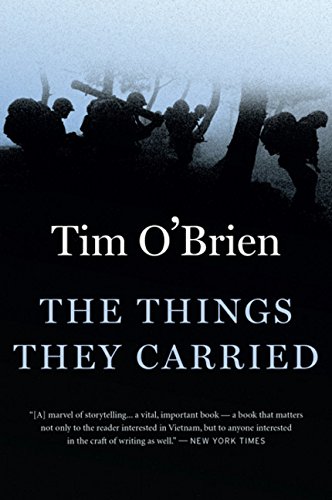

War has influenced much of what gets studied in college English departments across the country. Any survey course of British or American literature likely includes poetry from World War I poets like Siegfried Sassoon or Wilfred Owen. Compulsory military service in World War II meant that many writers served overseas, either before or after their writing careers took off. Kurt Vonnegut survived the bombing of Dresden as a prisoner of war, and William Golding participated in the D-Day invasion. Tim O’Brien’s novel The Things They Carried was based on his time as an infantry soldier in the Vietnam War.

Beyond just the written contributions of writers in uniform, two events in particular helped shape the contemporary literary scene in post-World War II America: Armed Services Editions of popular works (which democratized access to literature through mass produced pocket-sized editions of novels, short stories, and poetry; see Molly Guptill Manning’s excellent When Books Went to War for a detailed look at ASEs) ensured that soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and coast guardsmen—as well as Allied military and civilian populations— could read their way through The Great Gatsby or A Tree Grows in Brooklyn as they fought across Europe or the Pacific; and the Serviceman’s Readjustment Act (better known as the G.I. Bill) allowed millions of returning veterans the opportunity to attend college or vocational training, an opportunity they most likely would not have had otherwise. Taken together, the ASEs and G.I. Bill helped create a literate middle class.

After Vietnam, the military transitioned from draftees to volunteers. Combined with other factors—a generally robust economy, the drawdown after the breakup of the Soviet Union, and a general apathy towards military service—this meant that fewer and fewer people served or knew someone who served. This translated into fewer and fewer writers with military experience. By the time of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq (combat operations which continue in some form to this day), a handful of soldiers and other service members were deploying more and more frequently, and the disconnect between the military and civilian sectors of the population grew less and less able to speak a common language of experience.

A growing number of writers with military service are becoming part of the literary world. A large portion of the earliest writing could be deemed memoir or autobiography and presented their experiences in combat through straightforward and fact-based accounts; think Lone Survivor or American Sniper. At the same time, writers are fictionalizing or poeticizing their time in uniform and are expanding the meaning of “military literature.” Army veteran Brian Turner stands out as one of the preeminent post-9/11 war poets—he is a Lannan Literary Fellow and directs the low-residency MFA program at Sierra Nevada College. Phil Klay is a former Marine whose short story collection Redeployment won the National Book Award. Military writers are also bending conventions of genre; Colby Buzzell turned his blog My War: Killing Time in Iraq into a well-received book, and followed it up with Lost in America: A Dead End Journey, two works which parallel the longstanding tradition of examining the warrior at war and the warrior at home (see Homer: The Iliad and The Odyssey).

More and more attention is also being paid to the millions of men, women, and children who lived through the wars and occupations in Iraq, Afghanistan, and other countries.

Hassan Blasim’s short story collection The Corpse Exhibition: And Other Stories of Iraq comes from years of embargo, combat, and separation; Dunya Mikhail’s poetry likewise combines the voice of exile with lyrical and provocative passages; and The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini is only the most famous of a large and growing body of work from Afghan poets and writers. As more works are translated into English, more college students and readers will have the opportunity to study and learn from those who’ve lived through the terrible consequences of combat.

Military writing is also making its presence known in professional circles.

At the most recent Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP) Conference in Los Angeles, there were no fewer than twelve events featuring military writers who’ve served in Iraq, Afghanistan, or both. Veterans have also started projects such as The Veterans Writing Project, designed to promote and publish writing by those who’ve served; Military Experience and the Arts, which works to combine writing with visual art, dance, and therapy; and Line of Advance, one of many veteran-focused literary journals. Additionally, sites like Randy “Charlie Sherpa” Moore’s Red Bull Rising serve as aggregators of military and veteran writing contests, submissions, and events. Peter Molin runs Time Now, a source for critical analysis of a broad spectrum of military writing, including works from Iraqi, Afghan, and other overseas voices.

Much of the discussion on these sites (and others) focuses on ways forward, and a popular topic is the “civil-military gap”—the aforementioned inability of two segments of the American population to meaningfully communicate.

With fewer and fewer people serving or knowing anyone who has, misconceptions and prejudices abound on both sides. When much of the populace draws their knowledge of the military from movies (with varying levels of accuracy) or from lingering resentments handed down from a generation that lived through the Vietnam War, and when the shrinking number of veterans self-isolate or denigrate those who never served in uniform, how do we make sure we can still talk across the divide?

Perhaps colleges could include more contemporary writing by veterans. The canon could be updated to include writing men and women (who are making up more and more a critical portion of the military) who’ve deployed overseas or who’ve lived through invasion and occupation. Much of the same issues examined by Hemingway or Remarque or Homer are still relevant but could be contextualized through current writers.

A newly revamped Post-9/11 G.I. Bill is allowing a new generation of veterans an entry into the academic world. Contrary to what may or may not be popular conceptions of who these men and women are, they don’t all have PTSD, haven’t all seen combat, and aren’t all war mongers. (In fact, very few are.) Instead, these incoming college freshmen are generally older than their peers, have varied backgrounds and skills, and are eager to begin new chapters in their lives.

Conversely, veterans could look to their classmates for lessons from their own experiences. Many of them have served in other capacities, either in their communities or across the country and world. They are teaching in underserved schools, working in the medical fields, or volunteering in numerous ways. They are also the writers creating new and exciting works, often alongside the military writers.

““After all, what does literature do but teach us about what it’s like to live as someone else?””

College English courses could provide a unique venue in which to challenge the assumption that, because of different life experiences, veterans and civilians have an inherent difficulty in communicating. After all, what does literature do but teach us about what it’s like to live as someone else? How else can we understand anyone other than ourselves except through art and empathy? Perhaps by incorporating some of the growing community of military writers (as well as other communities; this could be a concept easily applied to women writers, writers of color, or queer writers) we could expand the notion of who is creating work worth reading and begin to learn again how to talk with our neighbors.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Travis Klempan is a Colorado native who joined the Navy to see the world. He found out most of it is water so he came back to the Mile High State. Along the way he earned a Bachelor's of Science (not Arts) in English from the Naval Academy and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing & Poetics from the Jack Kerouac School. He is currently pursuing teaching opportunities—adjuncting, substituting, and teaching at sea. He's also working on several pieces of writing at any given time, including a novel, a collection of fables, and a musical. He does not ski but makes a great road trip companion.

You can read the Dear English Major interview with Travis Klempan here!

What You Need to Know About Being a Young Freelance Writer

What is a freelance writer?

According to WritersBureau.com, “a freelance writer is a writer who works on a self-employed basis. They can work for just one magazine or, more often, they write for several different publications at a time. The more diverse a writer can be, the more likely they are to be published and paid for their work.”

I define freelance writing in a similar, but more personal way. To me, freelance writing is also a mode of advocating for one’s own voice to be heard. Freelance writing is utilized across a wide variety of literary and pop culture magazines, websites, and other publications. That being said, you probably read freelance writing all the time and don't even realize it. Many of the writers employed by some of the most popular publications, especially online, are in fact freelance.

The beauty of freelance, especially online, is that you can become part of a team, community or chapter from virtually anywhere, provided you have a computer and internet access. This appeals to many Millennials generally between the ages of 16-27, who have grown up accustomed to the instant communication that online activity offers us.

Why should I become a freelance writer?

First and foremost, freelance is becoming more and more accessible to people from all ages, cultural backgrounds, and socio-cultural groups. If there is a topic you are interested in—whether it be sports, music, politics fashion, etc.—chances are there is a popular or up-and-coming website just looking for writers! More established sites like Elite Daily, The Huffington Post, or Buzzfeed are such a hot commodity that they have works waiting to be published from hundreds of freelancers that do not necessarily promise a regular publishing schedule. Those sites are certainly worth the write; if you are published, having a piece published by a big name in the digital media world can carry that “wow” factor needed for impressing potential employers.

You should also consider writing freelance for the possibility of gaining exposure. Whether you are pursuing writing as a career or as a hobby, everybody wants his or her work to be seen. Applying to write for newer sites that are working out their kinks and are just now accruing their readership (and also may not have an extensive number of people on their writing team) is the best guarantee that your articles will be published on a weekly basis at minimum. Some people may be nervous about applying to low-profile websites due to their lack of notoriety, but doing so actually gives you the chance to attach your name to a start-up that could potentially become a game changer in the scope of digital media. Who doesn’t like being the one to start a new trend?

How do I become a freelance writer?

If you browse through a website, you will most likely find a "write for us," "contribute," “careers,” or "about" tab on the website that will allow you to apply for a writer position or get in contact with someone who can tell you about how to apply.

When you begin a freelance writing gig, you will initially be in contact with the editing or publishing manager of the website or magazine. These people will then most likely share various Google Drive documents, PowerPoints, and other paperwork that describes the mission of their publication or media site.

Why is online presence important?

Social media and online profile are both factors that heavily influence how you will be part of the freelance writing world as a young adult. A good online persona shows that you know your way around media. It should also demonstrate that you know how to advertise your interests and attract a following, both of which are important qualities and show that you have a good chance of attracting a readership. What you post, like, tag and share will speak volumes about you as an individual before anyone has even met you—if they ever will.

Your website, blog, Facebook page, Instagram, Twitter, etc. will all be indicators of the social circles that you have influence in. Additionally, online publishers will hire recruiters to look through social media hashtags, geotags, posts and locations to see what users may seem like promising contributors.

When you are hired, websites and magazines will definitely want you to share your work with your network!

What is it like to freelance in college?

If you’re still in school, try to find a website that suits your schedule, interests, and personal needs as a writer. Knowing how to balance freelance writing with school, family life, and extracurricular activities is important to both your overall physical and mental health, as well as to the quality of your writing.

Be conscious of the time you can dedicate to writing outside of school that may be unpaid, incentive-based or paid. For college students, most writing will be unpaid, as publishing freelance generally stems from interest and exposure, and not need of money.

Interested in starting your freelance career? Here are some examples of sites and magazines that use freelance writers (and are open to beginning writers!) :

- Elite Daily

- Odyssey Online (where you can now apply under my communities, “Manhattan, NYC” and “New Haven, Connecticut")

- Society 19

- Thrillist

Why should you consider freelance writing?

Figure out what interests you personally, where your writing passions lie, and what you like to write about. Having your writing online before applying to write for a website is important and key. If you already have your own personal work online for fun, people will be more inclined to hire you freelance if they can get an idea of the type of content you create (your form, writing style, aesthetic, etc.) and also what you specialize in as it relates to your major, hobbies, passions and career goals. Will you be looking for a poetry site, or are you interested in writing pop culture pieces? This will determine where you want to write. Becoming an “expert” in whatever field you inhabit will make potential hiring editors interested in what you have to say and how you use media to say it.

The best way to figure out whether writing online is for you is by trying out a whole bunch of sites and styles. Apply for a variation of publications that can teach you different methods of writing and will also challenge you to learn about new topics or see things from a new perspective. Getting out of your comfort zone will help you become more successful, more convincing, and more appealing to both hiring staff and readers.

* * *

““The digital media industry as it relates to freelance writing is a field where you don’t have to wait for publishers to give you the opportunity to write. You create those opportunities on your own by blogging, marketing yourself online, and reaching out to others who share your passions.””

As an English major and as a writer, freelancing has strongly impacted me; it has increased my love for writing and has pushed me out of my comfort zone in terms of style, tone and structure. It has also helped me become part of a community of other writers who want the same things I do, and it has given me mentors as well. There is a certain level of pride and accomplishment that exists in seeing your work being shared online. Freelancing as a young writer also gives you the opportunity to receive constructive criticism and positive feedback from peers, editors, and even strangers. The digital media industry as it relates to freelance writing is a field where you don’t have to wait for publishers to give you the opportunity to write. You create those opportunities on your own by blogging, marketing yourself online, and reaching out to others who share your passions. Writing for digital publications lets you learn about the online writing world, and is a fun hobby that can become a livelihood if people decide they like your writing.

For anybody on the fence, I would definitely say to give freelance writing a try. You have nothing to lose from giving it a test run, and you never know what could come of it!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wandy Felicita Ortiz

Originally from Brooklyn, New York and raised in northern New Jersey, Wandy Felicita Ortiz is a rising senior graduating cum laude with a Bachelor’s in French and English at St. John’s University in Queens, New York. In her studies, Wandy has developed a passion for digital media, Feminist literary theory, and poetry in both languages. A regular contributor and editor for Millennial platforms including Odyssey, Society19, and the all-female site Her Track, Wandy is excited to be discussing her expertise as a college freelance writer via her favorite website for English majors! You can also follow her @wanderingfelicity on Instagram, @wandyfelicita on Twitter, or shoot her an e- mail via her blog for more information on where and how to freelance. When she’s not rushing out of class to submit an article, you can find her watching the day’s sunset, dousing her quarter-life crisis in that third cup of coffee, or watching videos of cute dogs.

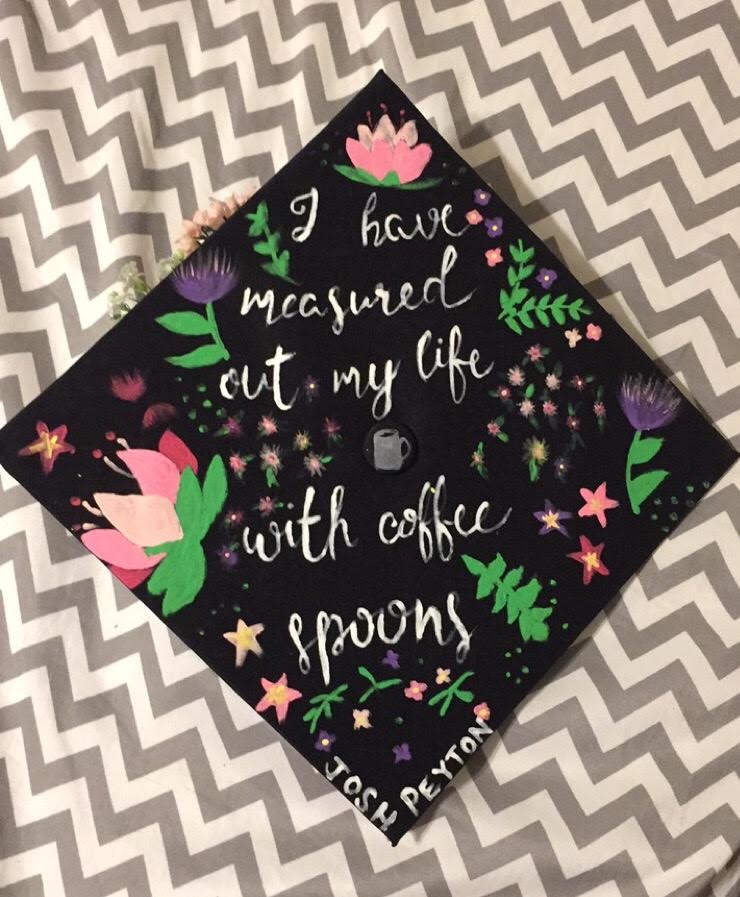

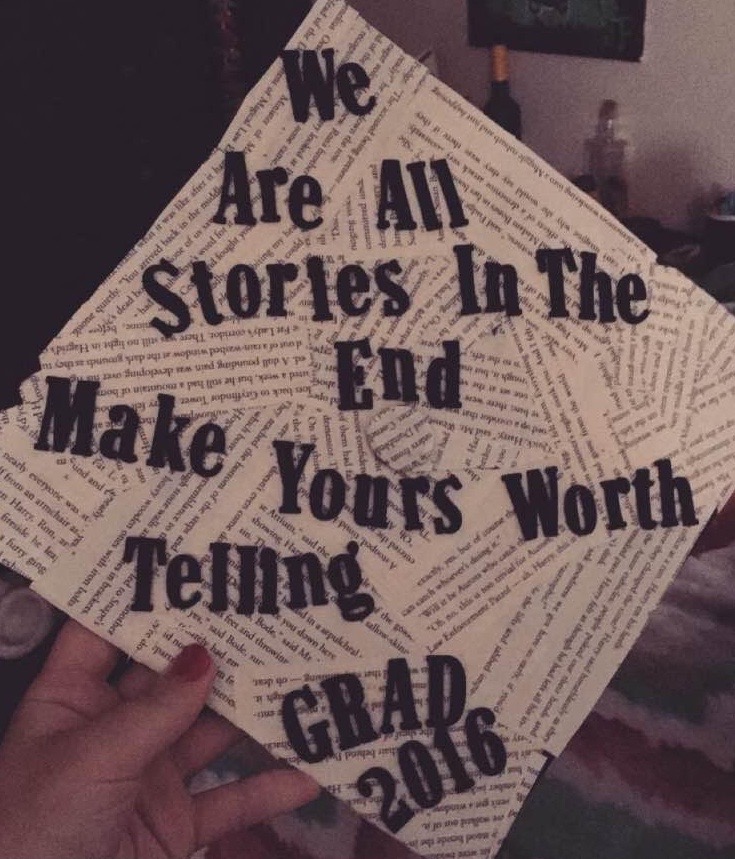

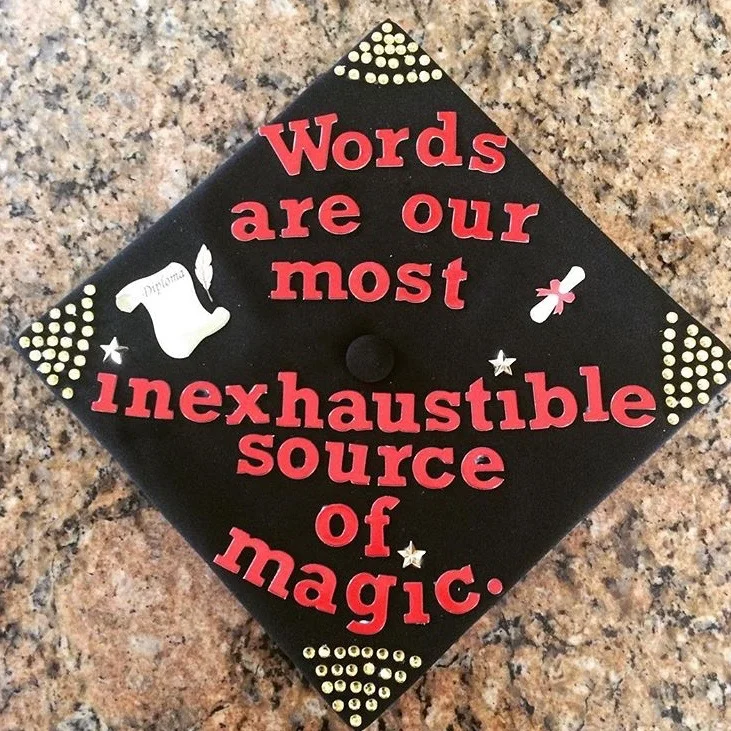

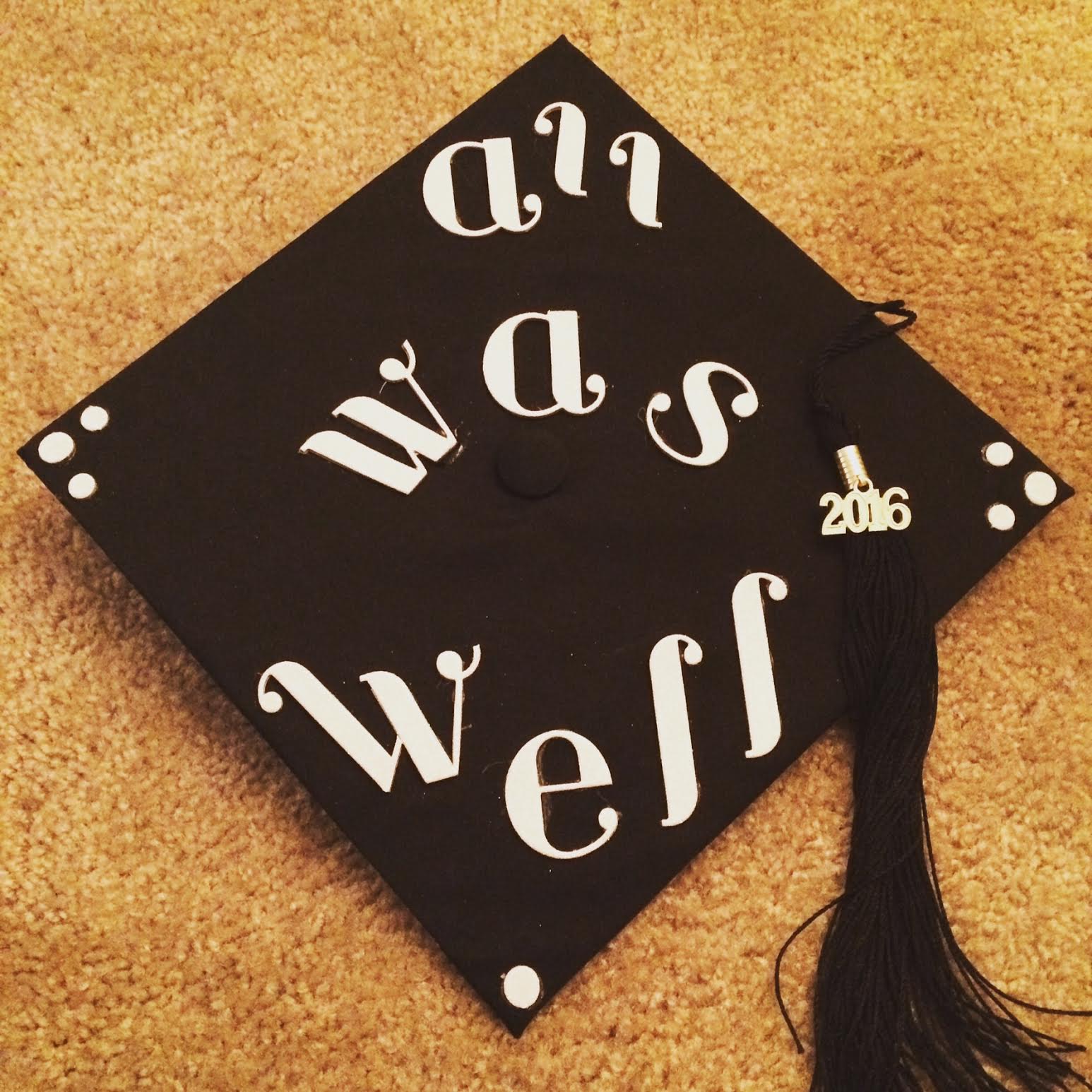

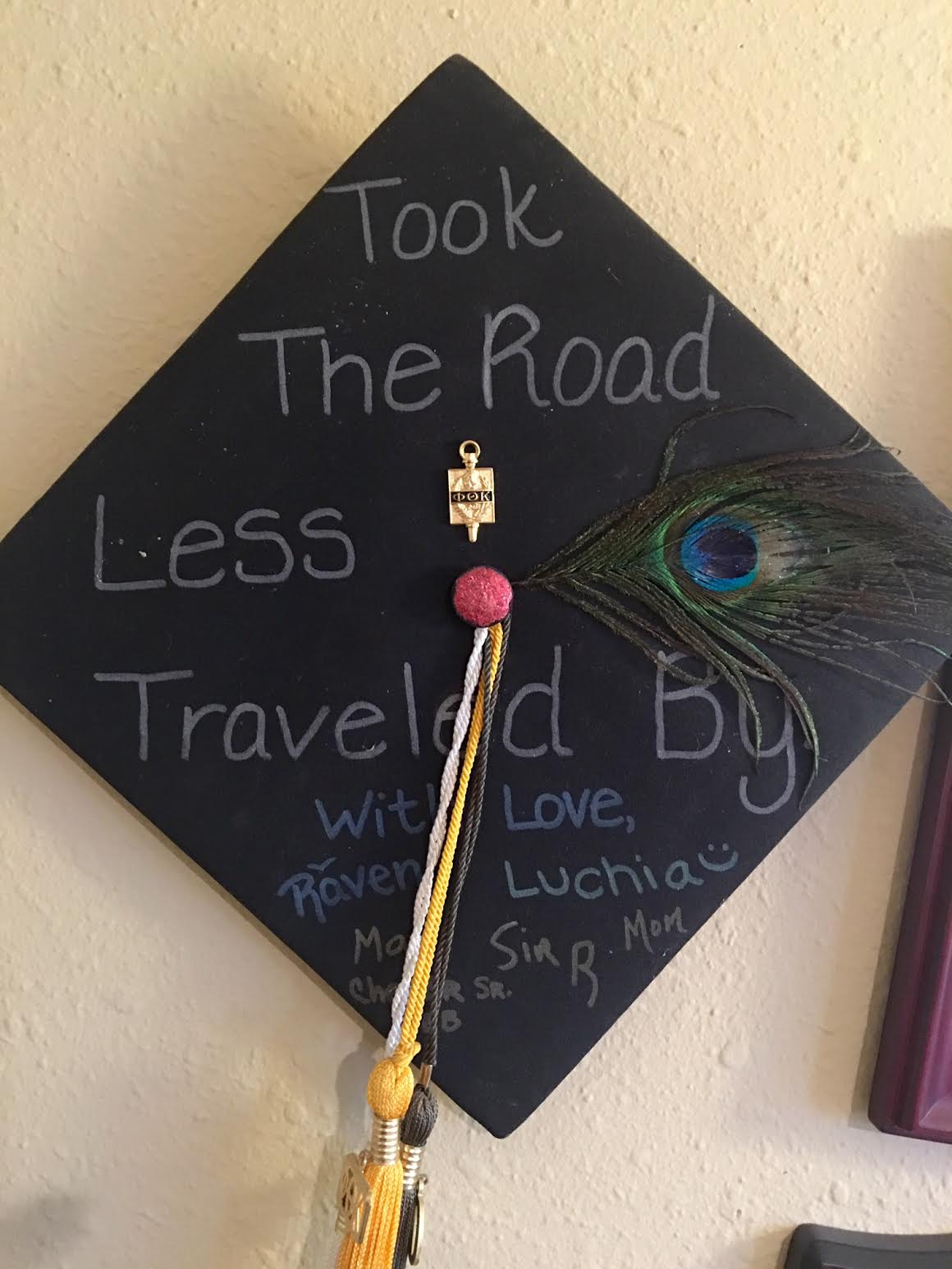

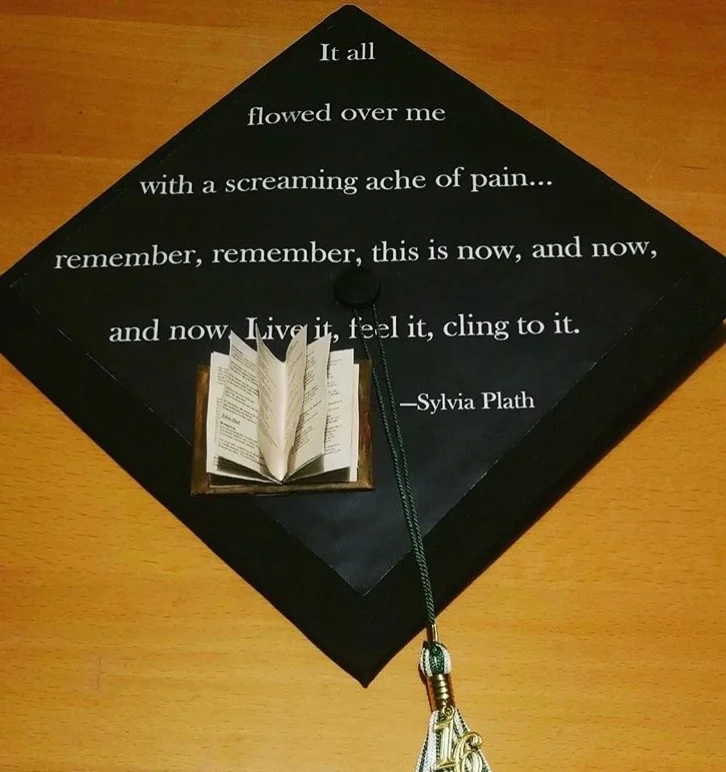

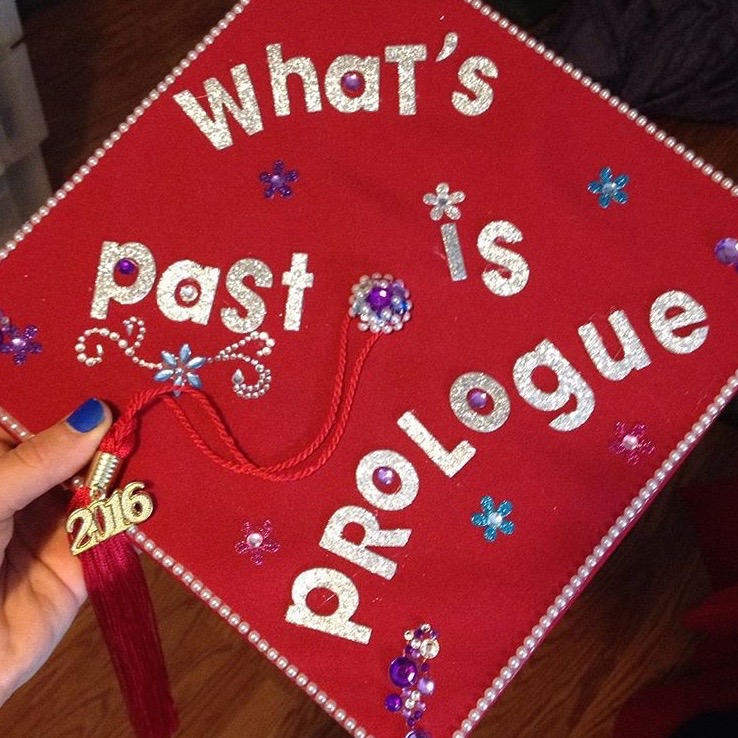

Graduation Cap Decoration Ideas for English Majors

Congratulations, graduates! The collection of beautifully decorated graduation caps below make our English major hearts soar with love for all things bookish, nerdy, and awesome. Big thanks to everyone who contributed their one-of-a-kind creations!

Created by Nguyet Tran

Created by Alaina Ray

Created by Sophia Vander Velde

Created by Maggie Young

Created by Holly Wood.

Created by Morgan D. Mears

Created by Emily Letoski

Created by Robert Hatch

Created by Tiffani Daniel

Created by Chelsea Pennington

Created by Michelle Noel

Created by Joe Rosemary

Created by Nina Mollard

Created by Rennie (Instagram user @ReeWriteMe)

Created by Samantha Curreli

Created by Mehgan Frostic

Created by Julia Woolever

Created by Brenda Nieves

Created by Noël Ormond

Created by Abigail Gruzosky

Created by Daniella

Created by Caitlyn Yohn

Created by Lauren Greulich

Created by Tiffany Fox

Created by Jennifer Kleinkopf

Created by Bieonica Parsons

Created by Amanda Bales

Created by Veronica Russell

Created by Mikayla Arciaga

Created by Ambs Magaña

Created by Jesse Cole

Created by Sterling Farrance

Created by Leia Johnson

Created by Jenna Caskie

"1,000 pearls of wisdom" - Created by Jenny Howard

Created by Whitney Jackson

Created by Ashley W

Created by Fallon A. Willoughby

Created by Stef Wasko

Created by Rachel Tallis

Created by Kimberly Rebecca

Created by Lisa Bosco